Part 3: The Fall and the Silence — How uMthwakazi Was Erased

“To destroy a nation, first erase its memory.”

Introduction: From Sovereignty to Subjugation

In the previous chapters, we traced the rise of uMthwakazi under King Mzilikazi kaMashobane — a sovereign, multi-ethnic kingdom forged through strategic alliances, migrations, and statecraft. However, the dawn of colonialism and subsequent political developments led to the systematic dismantling of this nation. This chapter delves into the deliberate erasure of uMthwakazi's identity, culture, and history, culminating in the Gukurahundi atrocities and the ongoing marginalization of its people.

The Colonial Conquest and the Fall of uMthwakazi

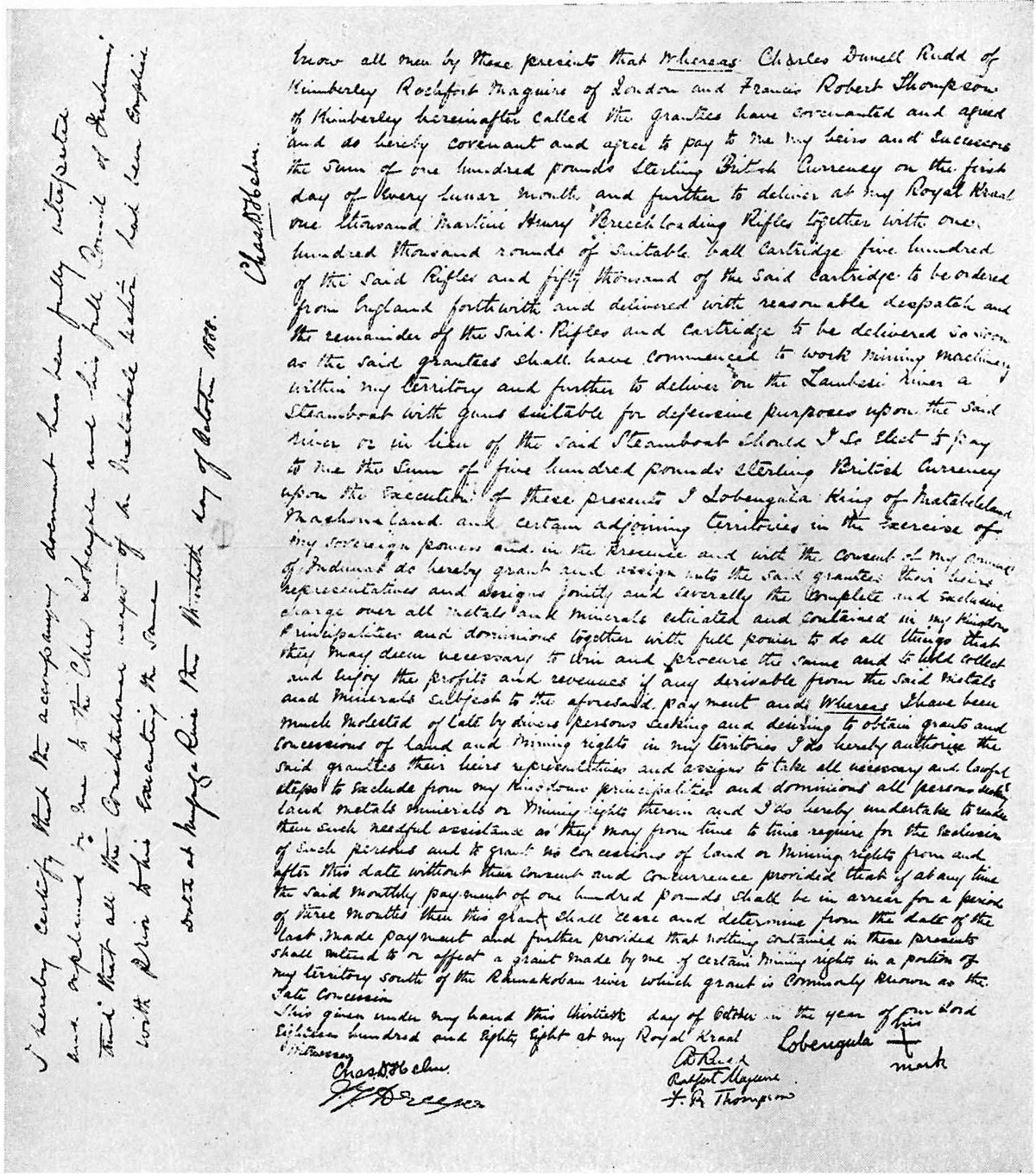

The Rudd Concession: A Masterpiece of Deception

On 30 October 1888, King Lobengula signed what he believed was a limited mineral rights agreement with three agents of Cecil Rhodes — Charles Rudd, James Rochfort Maguire, and Francis Thompson. In exchange for exclusive mining rights, he was to receive:

£100 per month

1,000 Martini-Henry rifles

10,000 rounds of ammunition

A riverboat for navigation

But this “Rudd Concession” was no ordinary deal — it became the colonial equivalent of a coup. Rhodes used it to secure a Royal Charter from the British government in 1889, giving his British South Africa Company (BSAC) full authority to administer and occupy vast territories — including uMthwakazi. Lobengula had not ceded sovereignty. He had been duped.

Upon discovering the deception, Lobengula sent envoys to Queen Victoria to repudiate the deal. But it was too late. Rhodes’ lobbying machine in London — and the imperial appetite for gold — rendered his objections invisible.

“What I have done I did not understand, but the words of the paper are not mine.”

— King Lobengula, in a letter to Queen Victoria

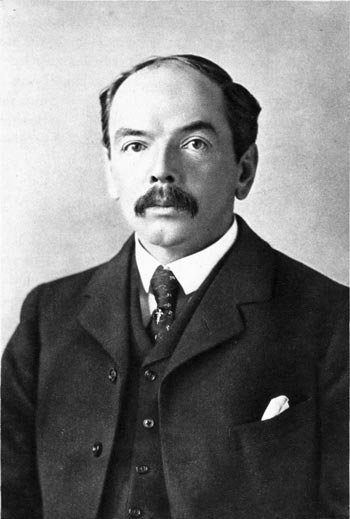

Jameson, the Pioneer Column, and the Copper Wire

Leander Starr Jameson, a close associate of Rhodes, led the next phase of occupation. In 1890, he directed the Pioneer Column into Mashonaland, establishing Fort Salisbury (present-day Harare), under the guise of protecting the Shona from Ndebele incursions.

In truth, the plan was always to seize Matabeleland.

A symbolic moment came when copper telegraph wires were laid across uMthwakazi lands. When Lobengula questioned the intrusion, he was told they were for peaceful communication. In reality, they were for expanding British colonial control.

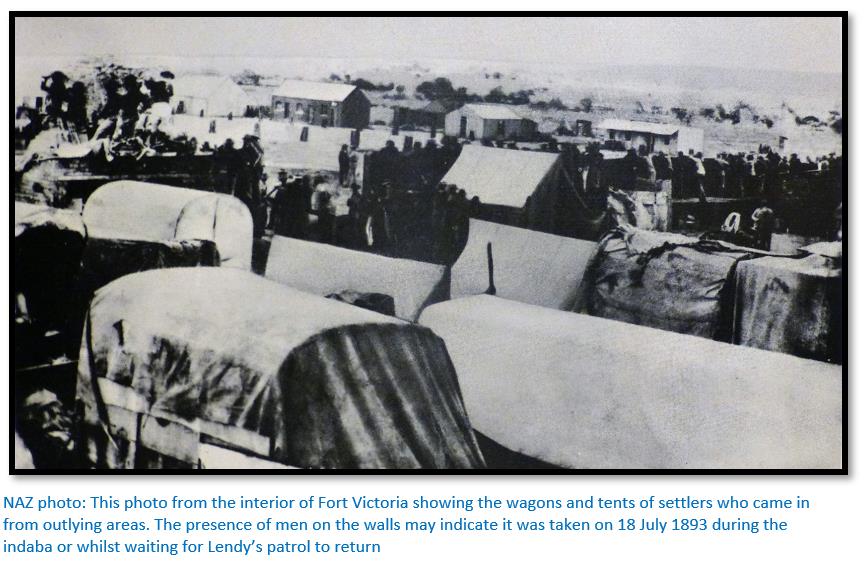

The Victoria Incident: Manufactured Justification for War

The final spark came in July 1893 — but not as many colonial records claim.

According to oral history and revised scholarship, including work by the Zimbabwe Field Guide and African historians, the so-called Victoria Incident was not an unprovoked Ndebele raid.

Instead, it began when subjects of Chief Gomara, a Shona leader, stole 500 yards of copper telegraph wire laid across uMthwakazi territory.

The BSAC accused Lobengula’s people and seized cattle in retribution. Lobengula, enraged that his kingdom had been falsely punished, sent a regiment to retrieve both the copper and his cattle.

When the Ndebele regiment arrived, they were resisted by Shona villagers near Fort Victoria. A skirmish broke out, resulting in several deaths — not because the Ndebele were attacking the settlers, but because they were retaliating against theft in their own land.

Jameson seized this as a golden opportunity.

“The moment we’ve been waiting for,” he is said to have remarked.

Using the incident as a casus belli, Jameson and the BSAC launched a full-scale invasion — despite no formal war being declared.

Umvukela and the Fall of uMthwakazi

In October 1893, the British South Africa Company mobilised its forces, armed with Maxim machine guns, and launched the First Matabele War.

The Ndebele, though fierce, were overpowered by superior firepower.

Bulawayo was set ablaze by its defenders to deny it to the enemy.

Lobengula fled north, dying under mysterious circumstances in early 1894.

By mid-1894, uMthwakazi had fallen. The British South Africa Company declared it open territory, parcelled it out to settlers, and rewrote the land’s identity. It was no longer uMthwakazi — it was now called “Matabeleland” under Company rule.

Gukurahundi: The Blood Price of Silence

From 1983–1987, the Zimbabwean government launched a brutal campaign against Matabeleland and Midlands provinces, known as Gukurahundi — a Shona term for “the early rain that washes away the chaff.”

Over 20,000 civilians — mostly Ndebele — were murdered by the North Korean-trained Fifth Brigade.

Victims were burned alive, buried in mass graves, raped, and mutilated.

Churches, schools, and homesteads became killing fields.

The stated goal was to eliminate “dissidents.” But as the Breaking the Silence report by the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace (1997) states:

“The majority of those targeted were civilians. Gukurahundi was a political operation designed to silence ZAPU and redraw the balance of power.”

Lobengula’s descendants were not just conquered — they were massacred.

And the world looked away.

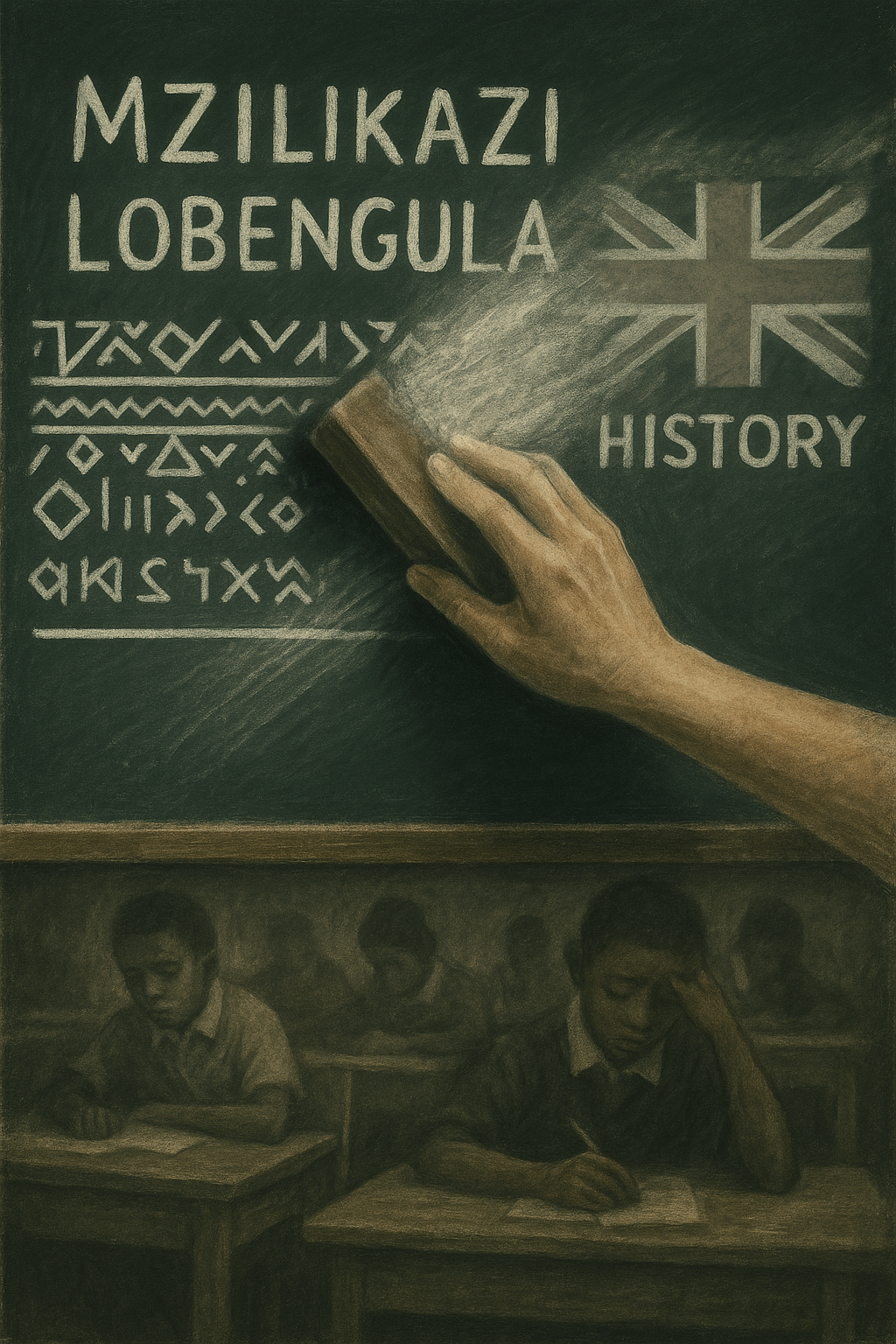

The Tools of Erasure: Language, Education, and Curriculum

See: “The 1979 Grand Plan: Blueprint or Backfilled Myth? An Objective Analysis for uMthwakazi” for a full breakdown of these policies and their origins.

After the blood dried, the state sharpened its next weapon: erasure.

Shona-speaking teachers were deployed en masse to Matabeleland — many unable or unwilling to teach in isiNdebele.

Textbooks glorified Shona leaders, sidelining Mzilikazi, Lobengula, and the entire history of uMthwakazi.

This was not benign neglect.

This was the death of a nation in the classroom.

“They erased us with a chalkboard, not a rifle.”

— Elder, Insiza District

These mechanisms were identified and dissected in multiple reports and oral testimonies, many of which were already covered in our Grand Plan exposé.

Selective Recognition: The Two Kings Paradox

(Previously explored in our critique of the state’s selective cultural tolerance.)

To understand how memory itself is feared, consider the two monarchs:

King Bulelani kaLobhengula, heir to uMthwakazi’s throne, was met with resistance, ridicule, and state interference.

Timothy Chiminya, self-declared King Munhumutapa, was embraced with national airtime — until he dared to call for real authority.

As discussed in Part 1, this contrast isn’t just about legality. It’s about which histories the state allows to be celebrated — and which it tries to bury.

Conclusion: We Are the Memory

They burned our kraals.

They buried our kings.

They erased us from syllabi.

But we are still here.

We are not the bitterness they accuse us of — we are the memory they fear.

We remember.

We rise.

We roar.

Vuka Mthwakazi! ✊🏽