Part 1: uMthwakazi - The Kingdom They Tried to Erase

A nation is not lost when its land is taken — it is lost when its children forget its name.

Introduction

Ask a young person in Zimbabwe today what uMthwakazi is, and most will either shrug or speak vaguely of the Mthwakazi Republic Party (MRP). Some associate the term with bitterness, old war veterans, or exiled politicians. But very few — even among the youth of Matabeleland — truly understand that uMthwakazi was once a thriving, diverse, and sovereign kingdom.

The name has been erased from textbooks, history lessons, maps, and national discourse. What remains is a ghost — Matabeleland, a colonial name stitched in place of a royal identity.

This blog post — the first in a three-part series — seeks to awaken the spirit of that name. To tell the truth that history books have buried. To remind abaThwakazi who they are, and where they come from.

Mthwakazi Is Not Matabeleland

Before colonisation, there was no such place as Matabeleland. That name came later — an anglicisation of amaNdebele, used by colonial officials to label the kingdom of Lobengula after its violent conquest.

The real name was uMthwakazi.

The boundaries of uMthwakazi were well-defined. They stretched from the Limpopo River in the south to near the Zambezi in the north, from the Kalahari in the west to the Umnyathi River in the east — what later became known as the Jameson Line. That line was used by colonisers to separate uMthwakazi from Mashonaland.

The name uMthwakazi itself has deep meaning. Oral tradition suggests it honours the indigenous San (AbaThwa) people and that the kingdom’s name means “land of the Thwa.” Others interpret it as “the owner of the state.” Other historians talk about a Mu-Thwa Queen who healed King Mzilikazi's feet when they had blistered and inflamed from his ceaseless trek. Regardless of etymology, it was the name that King Mzilikazi kaMashobane gave to the multi-ethnic nation he forged.

“It is a formal and well-known geopolitical name for the traditional nation-state of the Ndebele in the 19th century.”

— Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni (The Ndebele Nation, 2008)

A Kingdom of Many Nations

One of the greatest lies ever told about amaNdebele is that they were a single tribe. That’s colonial thinking. In truth, uMthwakazi was a multi-ethnic kingdom made up of many nations.

By the 1840s, it comprised three broad groups:

AbeZansi – the Nguni core of Mzilikazi’s army and aristocracy.

AbeNhla – Sotho-Tswana and Pedi people who joined during the migration.

AmaHole – the local Rozvi, Kalanga, Tonga, Venda, Nyubi, Nambya, and others already living in the land.

Together, they built a kingdom.

Mzilikazi didn’t merely conquer. He unified. He gave status, land, protection, and a new national identity. All these groups were known collectively as uMthwakazi.

Today, there are over 13 indigenous languages (Ndebele, Kalanga, Tonga, Venda, Sotho, Nambya, Tswana, Xhosa, Chewa, Doma, Lozi, Nyubi, Hlengwe) within Matabeleland. That is not by accident — it is by legacy. uMthwakazi was always a federation of nations, with isiNdebele serving as the common language, much like Swahili in East Africa.

How Mzilikazi Built uMthwakazi

Mzilikazi didn’t find an empty land. When he arrived in the late 1830s, the region had been destabilised by previous waves of conflict. Leaders like Zwangendaba, Nyamazana, and others had already scattered the once-powerful Rozvi Empire.

What remained was a shattered region, fertile and vast, but lacking leadership.

Mzilikazi filled that void.

He sent his lieutenants ahead (notably Gundwane Ndiweni), established military kraals, and built a capital at koBulawayo. He introduced regimental systems, a tribute economy, and chieftainships that integrated existing local leaders.

“By 1840, King Mzilikazi’s authority stretched from the Limpopo in the south to the Umnyathi in the east… uMthwakazi was sovereign and secure.”

— Pathisa Nyathi (Igugu LikaMthwakazi, 1994)

This was no tribe. This was a state.

Colonial Conquest and the Death of a Name

In 1893, the British South Africa Company invaded. King Lobengula, son of Mzilikazi, was deceived, betrayed, and eventually defeated. The kingdom of uMthwakazi fell, its capital was razed, and its people subjected to colonial rule.

The British renamed the land Matabeleland and absorbed it into Southern Rhodesia.

The term uMthwakazi vanished from official use.

Only in oral tradition and royal memory did the name survive.

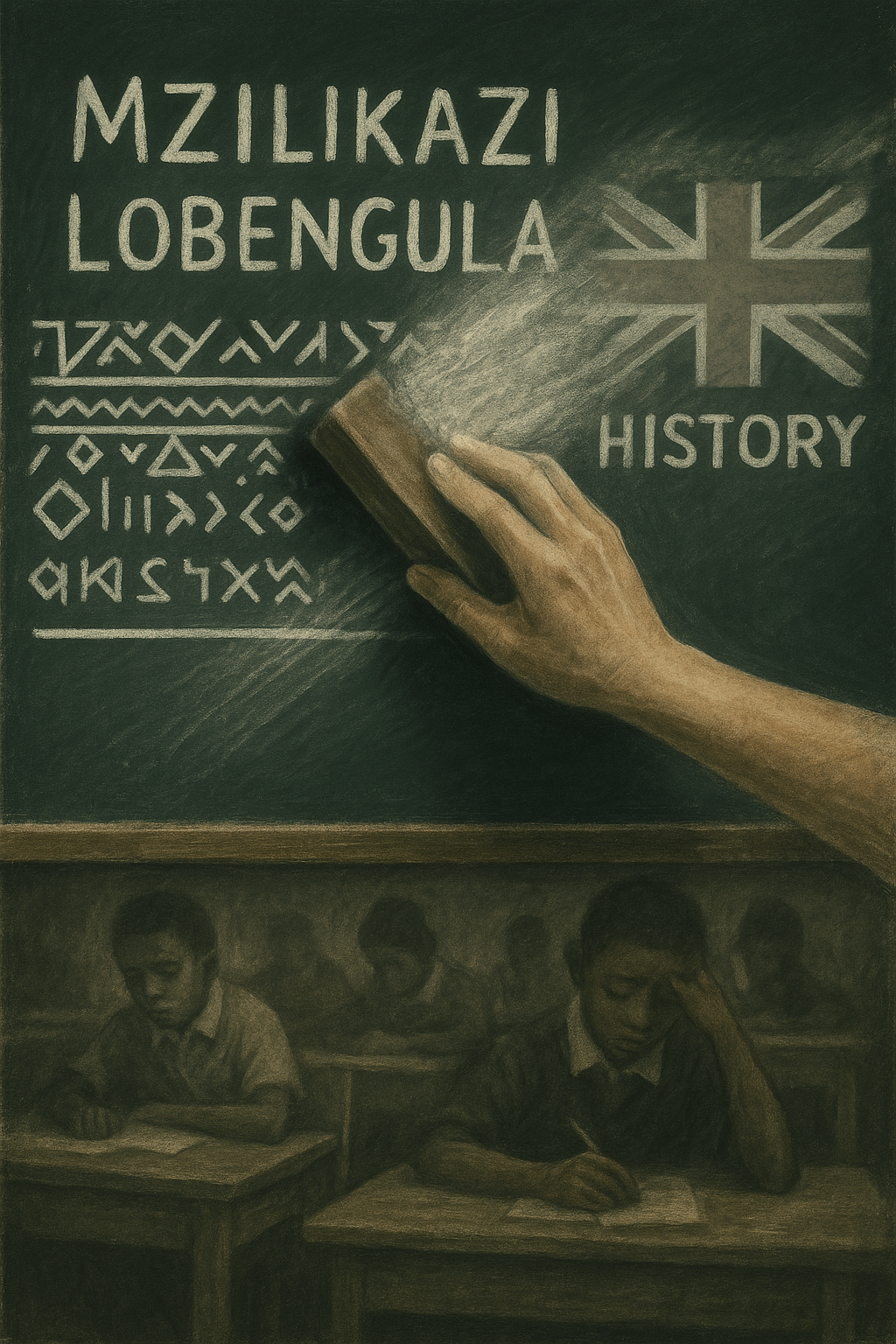

Erased from Textbooks, Erased from Memory

After independence in 1980, Zimbabwe did not restore uMthwakazi. In fact, it buried it deeper.

Ask yourself: where in the national curriculum is uMthwakazi mentioned?

Textbooks speak only of “Matabeleland.”

The Mfecane and Ndebele Kingdom are reduced to warlike raids.

No mention is made of Mzilikazi’s diplomacy, statecraft, or diversity.

The 13 languages of Matabeleland are omitted or grouped under “minority.”

Even respected historians like Pathisa Nyathi — who have written dozens of books on Ndebele history — are excluded from the official curriculum.

“Locally patriotic texts written in isiNdebele are not used in schools… they are not even prescribed.”

— Ndlovu-Gatsheni (The Ndebele Nation)

In effect, uMthwakazi was erased from the minds of its children.

Why This Matters Now

Reclaiming uMthwakazi is not about politics.

It is about identity. It is about remembering that we — the children of Matabeleland — are more than just victims of Gukurahundi or footnotes in national history.

We are descendants of kings, builders of a multi-ethnic kingdom, and custodians of a rich cultural heritage.

To revive uMthwakazi is to revive pride.

“They buried the name. Not the nation. We are the resurrection.”

Coming Next: Part 2 — The Lion King of the Plateau: uMzilikazi kaMashobane

We’ll explore how Mzilikazi, born a Khumalo prince, became one of Africa’s most brilliant state-builders, and how his legacy lives on even in our modern day.