Part 2: The Lion King of the Plateau - uMzilikazi kaMashobane

“A true king does not inherit a crown — he carves it from the bones of chaos.”

Introduction: Not Just Shaka’s General

For decades, King Mzilikazi kaMashobane has been painted as a deserter of uShaka kaSenzangakhona, and a fierce warlord who raided his way into Zimbabwe. That’s the version of history often told in Zimbabwean textbooks.

But in truth, Mzilikazi was more than a general — he was one of Southern Africa’s most brilliant state-builders. He didn’t just flee Zululand. He carved an empire from the ruins of the Mfecane. He didn’t just conquer tribes — he built a nation from over 13 ethnic groups, united by language, military discipline, and shared law.

In this chapter, we trace his full journey — from Zululand, through South Africa, Botswana, Mozambique, and even into Zambia — until his triumphant return and founding of uMthwakazi, the kingdom they tried to erase.

Royal Blood and the Shadow of Zwide

Mzilikazi kaMashobane was born around 1790 to Mashobane kaMangethe, leader of the Khumalo, and Nompethu kaZwide, daughter of the Ndwandwe king Zwide kaLanga. This made him both Khumalo and Ndwandwe — royal on both sides. He grew up in a kingdom torn between giants: Dingiswayo’s Mthethwa and Zwide’s Ndwandwe.

In 1817, after Shaka escaped a trap laid by Zwide, Mashobane was executed by Zwide. His son, Mzilikazi, fled with a core group of the Khumalo to Shaka’s growing empire.

Shaka, impressed by Mzilikazi’s loyalty, wisdom, and military prowess, made him a commander — and gave him command of the Khumalo regiment within the Zulu army. But Mzilikazi was not born to serve forever. His destiny lay elsewhere.

The Alliance with Shaka — Two Kings, Two Visions

Before colonisation, before conquest, there was respect.

The alliance between King Mzilikazi kaMashobane and King Shaka kaSenzangakhona is often misrepresented as one of subordination. Zimbabwean and even South African textbooks frequently label Mzilikazi a deserter — a Zulu who ran.

But we were never Zulu, we are aMahlabezulu.

We were amaNtungwa — a royal Nguni clan with roots that predate the rise of the Zulu kingdom. Even during our military alliance with the Zulu under Shaka, we retained our identity, our regiments, and our royal lineage. We were Khumalo — not a sub-clan, but a parallel house with its own legacy.

“What Shaka was to KwaZulu, Mzilikazi became to Mthwakazi.”

The alliance was born out of mutual interest — to destroy the Ndwandwe and their ruthless king, Zwide kaLanga. Mzilikazi had every reason to seek revenge: Zwide had executed his father, Mashobane kaMangethe, and tried to control him as a puppet leader. Shaka too sought revenge — Zwide had killed his mentor, Dingiswayo.

Together, they trained, strategised, and crushed the Ndwandwe. It was Mzilikazi’s tactical plan — using psychological warfare (Ndwandwe war songs) and terrain-based flanking — that led to their most decisive victory.

A Split of Purpose, Not Betrayal

Once Zwide was defeated, their mutual goal was complete. What came next was inevitable: both kings needed to pursue their own destinies.

Mzilikazi did not "flee" — he migrated.

The tensions between him and Shaka were political, not personal. Oral tradition and battlefield evidence suggest that when Mzilikazi left with his people, Shaka sent Zulu regiments to pursue him. But those engagements — like the battles near the Crocodile River and in the highveld — ended without clear victories.

This tells us two things:

They were evenly matched.

After years of fighting together, training together, and learning each other’s strengths and tactics, neither king could decisively outmanoeuvre the other. Mzilikazi’s regiments, though fewer in number, held their own against larger Zulu forces.Shaka may have let him go.

Mzilikazi was not a rebel. He was a brother in arms. Shaka could have sent waves of regiments to crush him — and with his numbers, perhaps eventually succeeded. But he didn’t. He sent enough to make a point — to assert strength — but stopped short of annihilation.

It’s possible Shaka understood what Mzilikazi was doing: building his own legacy, just as he had done in Zululand.

“Shaka may have seen Mzilikazi as the one man he could not destroy without breaking something sacred.”

This decision — to let Mzilikazi go — may have contributed to the mounting tensions in Shaka’s court. His aunt, uMkabayi kaJama, who had long opposed his leadership decisions, viewed it as a sign of weakness. Within a short time, Shaka was assassinated, and his brother Dingane took the throne.

The Trek Begins — A New Moses in the Wilderness

What followed was one of the most epic migrations in African history.

Mzilikazi kaMashobane led his people — regiments, families, artisans, cattle herders, and spiritual leaders — northward through:

Mpumalanga and Gauteng, where he established a base at eNkungwini (“Place of Mist”).

Waged battles and integrated Sotho, Tswana, Pedi, and Venda communities.

Created a hybrid society united under the Khumalo crown.

Used military and diplomatic skill to integrate peoples — not just defeat them

This journey was not a chaotic flight — it was a strategic, deliberate march toward sovereignty.

Exile Turned Empire — The Great Trek North

Drawing from Nthebe Molope’s King Mzilikazi kaMashobane, we trace the vast reach of this migration:

South Africa :

From eNkungwini, he led conquests and built alliances. He was challenged by Boer Voortrekkers at Vegkop and Mosega, holding his ground until it became tactically prudent to move north.Botswana:

After crossing the Limpopo, he faced hostile terrain and the tsetse fly — but left an imprint through small settlements and merged tribes.Mozambique, Zambia, Namibia:

Oral and archival records suggest periods of regrouping in Kaokoland and the Zambezi basin. Mzilikazi was avoiding colonial contact while building diplomatic ties with frontier communities.Zimbabwe (Matabeleland):

By the late 1830s, he arrived in a fractured land. The Rozvi empire had collapsed. Zwangendaba and Nyamazana had swept through. Mzilikazi established koBulawayo, the capital of a new kingdom: uMthwakazi.

“He didn’t conquer a people — he organised a nation.”

Buy Nthebe Molope’s book to experience the full, richly detailed journey.

By 1840, Mzilikazi kaMashobane had established a federated kingdom made up of: amaNtungwa, Zulu, Swati, Sotho, Pedi, Tswana, Kalanga, Rozvi, Nambya, Shona, Tonga, and others. He unified them under one military system, one law, one economic model.

This was not a tribal chiefdom.

It was a state.

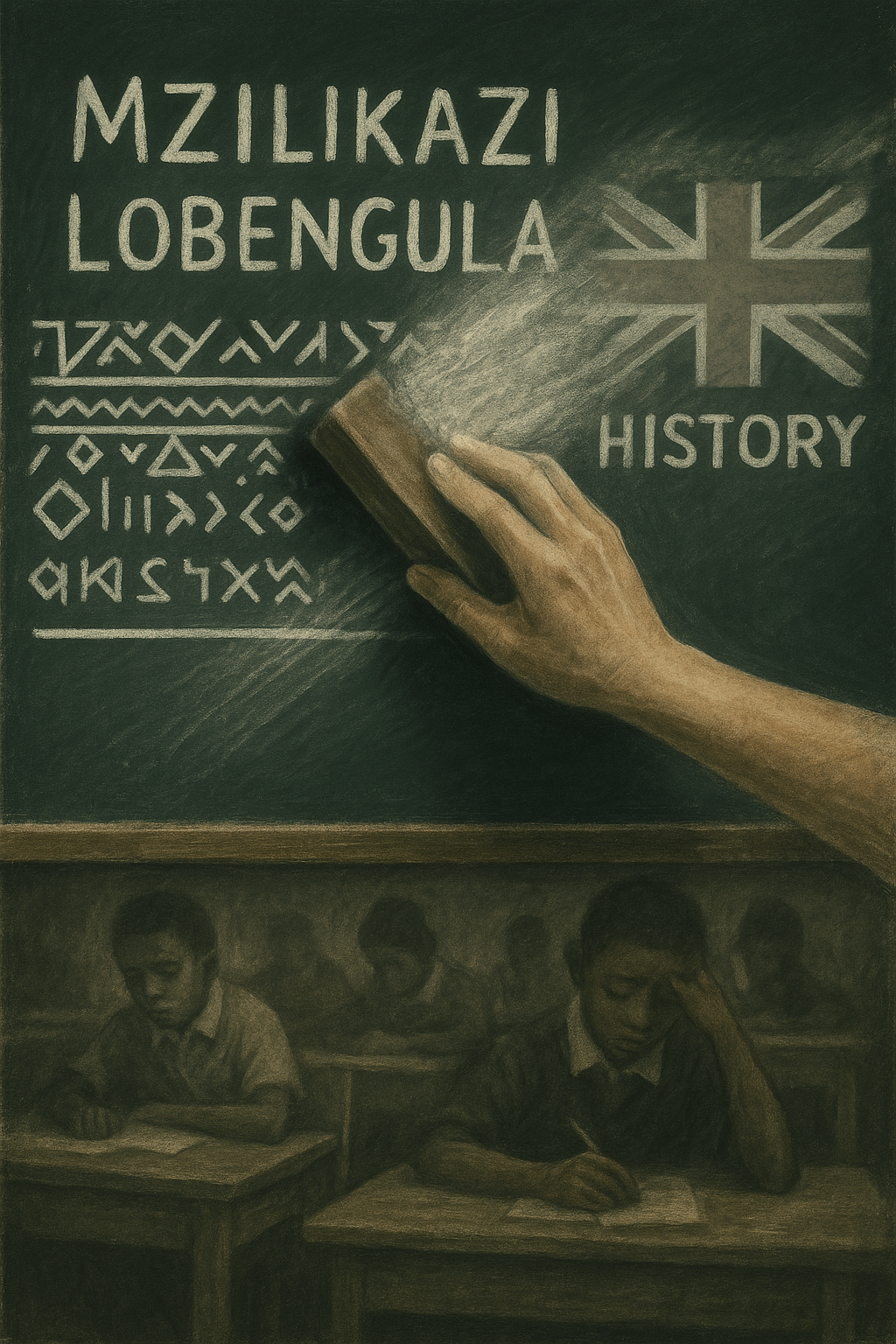

A Legacy Distorted by Erasure

Modern Zimbabwean curricula erase this legacy:

Mzilikazi is portrayed only as a raider.

The word “uMthwakazi” is absent.

The rich nation he built is reduced to “Matabeleland” — a colonial label.

But history, when reclaimed, tells a different story.

“He built a multicultural African empire that rivalled any kingdom of his age.”

Conclusion: Mzilikazi Still Lives

King Mzilikazi kaMashobane lives in our language.

In our resilience.

In our memory.

He lives every time we say "uMthwakazi" with pride.

He is not just our founder.

He is our blueprint.

Sources & Suggested Reading

Nthebe Molope, King Mzilikazi kaMashobane (2020)

Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, The Ndebele Nation (2009)

Pathisa Nyathi, Igugu LikaMthwakazi (1994)

Terence Ranger, Violence and Memory (2000)

Please support these historians by buying and reading their works. We stand taller on their shoulders.